Scribbled at the top of Information Management: A Proposal was tacit approval:

With that, physicist and computer programmer Tim Berners-Lee was free to pursue his vision of a new (what would be) global hypertext network connecting computers and people to each other in a dense and redundant network without which contemporary life seems almost impossible. But in 1990 it was only a simple, perhaps counterintuitive, scheme for connecting scientists and their documents to one another at the European Center for Particle Physics (CERN) on the outskirts of Geneva, Switzerland.

Berners-Lee arrived at CERN in 1980 and was surprised to discover that information about what computer was where, how to locate a specific software module, or who had done what with whom and when was hard to find. By 1989, his proposal for what to do about it described the situation:

Berners-Lee imagined a network with “anything being potentially connected with anything.” When he received the green light in November 1990, he was already implementing a prototype hypertext reading and writing software he named WorldWideWeb. (He’d considered a couple of other acronyms including The Information Mine (TIM) and Mine Of Information (MOI) but rejected both as a bit narcissistic.) Here’s a screenshot of the software running on his NeXT Computer workstation (which was also the first web server on the Internet):

Today, you can run his WorldWideWeb software and surf the internet like it’s 1990 here in an emulator. But at the time WorldWideWeb ran only on Berners-Lee’s specific machine and the very limited number of similarly configured NeXT computers, so it wasn’t so useful. To make the web more accessible, a line-mode browser was developed at CERN by 1991 which ran in a text-only terminal, on most unix computers, and requiring very little power. (You can also test-drive this software in an emulator here which evolved into Lynx, a text-only browser that still works on contemporary machines.) The line-mode browser was a strict hypertext environment, with links identified by numbers in brackets like this [1]. It was fast and simple and started to realize Berners-Lee’s original intuition:

Continues in class ...

With that, physicist and computer programmer Tim Berners-Lee was free to pursue his vision of a new (what would be) global hypertext network connecting computers and people to each other in a dense and redundant network without which contemporary life seems almost impossible. But in 1990 it was only a simple, perhaps counterintuitive, scheme for connecting scientists and their documents to one another at the European Center for Particle Physics (CERN) on the outskirts of Geneva, Switzerland.

Berners-Lee arrived at CERN in 1980 and was surprised to discover that information about what computer was where, how to locate a specific software module, or who had done what with whom and when was hard to find. By 1989, his proposal for what to do about it described the situation:

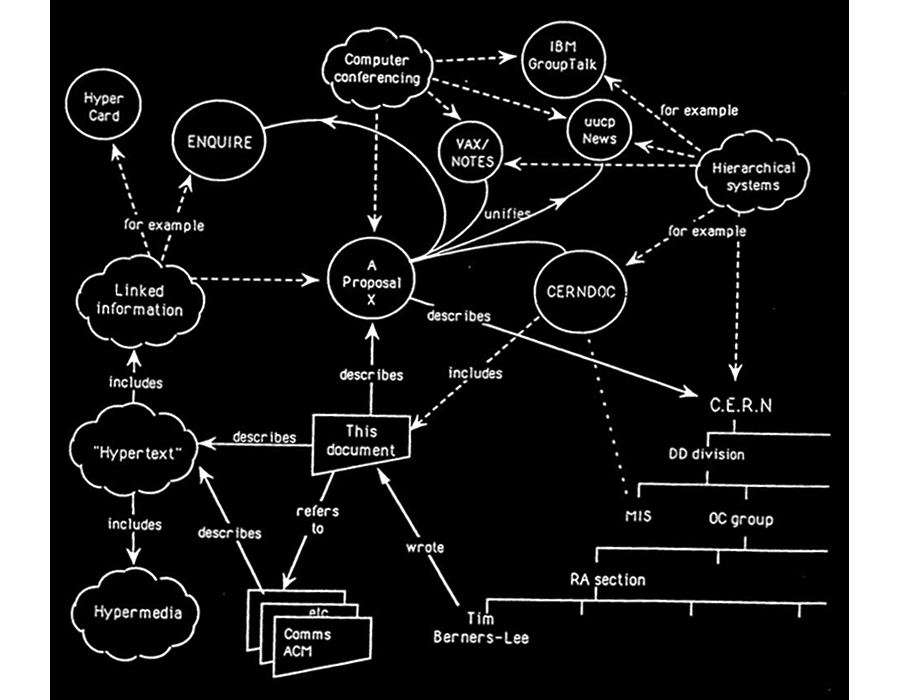

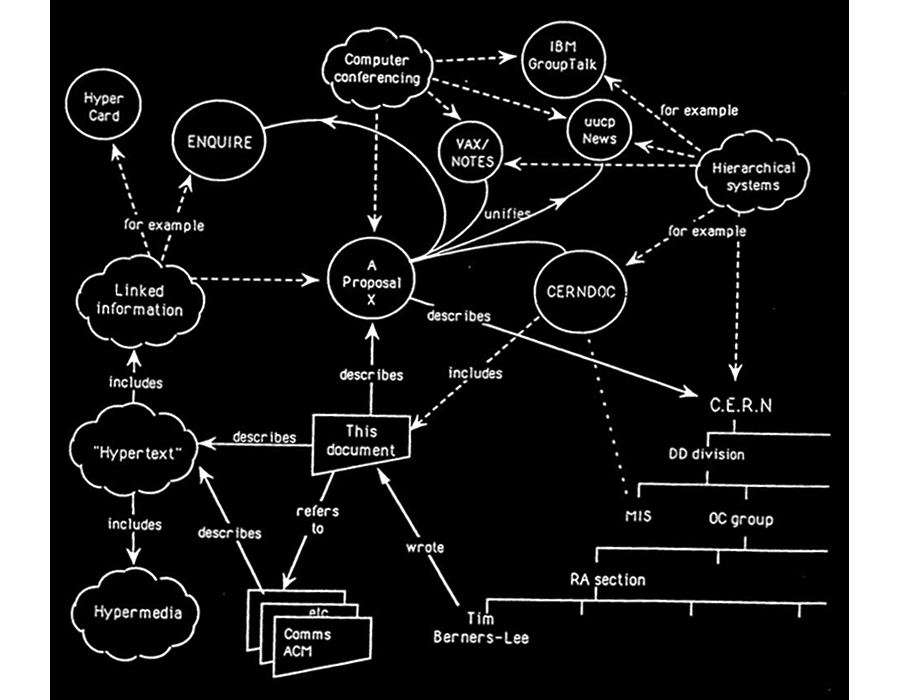

CERN is a wonderful organisation. It involves several thousand people, many of them very creative, all working toward common goals. Although they are nominally organised into a hierarchic management structure, this does not constrain the way people will communicate, and share information, equipment and software across groups. The actual observed working structure of the organisation ts a multiply connected “web” whose interconnections evolve with time.And he reasoned that if the actual organization was a densely connected web, then the information management system should mirror that structure. He included this diagram of mixed people, computers, and documents on the first page of his proposal to show what he meant.

Berners-Lee imagined a network with “anything being potentially connected with anything.” When he received the green light in November 1990, he was already implementing a prototype hypertext reading and writing software he named WorldWideWeb. (He’d considered a couple of other acronyms including The Information Mine (TIM) and Mine Of Information (MOI) but rejected both as a bit narcissistic.) Here’s a screenshot of the software running on his NeXT Computer workstation (which was also the first web server on the Internet):

Today, you can run his WorldWideWeb software and surf the internet like it’s 1990 here in an emulator. But at the time WorldWideWeb ran only on Berners-Lee’s specific machine and the very limited number of similarly configured NeXT computers, so it wasn’t so useful. To make the web more accessible, a line-mode browser was developed at CERN by 1991 which ran in a text-only terminal, on most unix computers, and requiring very little power. (You can also test-drive this software in an emulator here which evolved into Lynx, a text-only browser that still works on contemporary machines.) The line-mode browser was a strict hypertext environment, with links identified by numbers in brackets like this [1]. It was fast and simple and started to realize Berners-Lee’s original intuition:

Suppose all the information stored on computers everywhere were linked I thought. Suppose I could program my computer to create a space in which anything could be linked to anything. All the bits of information in every computer at CERN, and on the planet, would be available to me and to anyone else. There would be a single, global information space. Once a bit of information in that space was labeled with an address, I could tell my computer to get it. By being able to reference anything with equal ease, a computer could represent associations between things that might seem unrelated but somehow did, in fact, share a relationship. A web of information would form.Working from that software running on his local workstation and across a local network, Berners-Lee staged the first website on the internet and developed a set of digital protocols which remain the technical foundation of the World Wide Web today. These include HTML (Hypertext Markup Language), HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol), and URL (Uniform Resource Locator). His imagined version of what would become an impossibly connected global web was remarkably complete. He described it years later in his technical memoir-of-sorts, Weaving the Web:

In an extreme view, the world can be seen as only connections, nothing else. We think of a dictionary as the repository of meaning, but it defines words only in terms of other words. I liked the idea that a piece of information is really defined only by what it’s related to, and how it’s related. There really is little else to meaning. The structure is everything. There are billions of neurons in our brains, but what are neurons? Just cells. The brain has no knowledge until connections are made between neurons. All that we know, all that we are, comes from the way our neurons are connected.

Continues in class ...

February 2, 2026

Vague, but exciting . . .

https://princeton.zoom.us/j/98140026448?pwd=ZRjRgODHimRf47QaPKXXCZDUP9S36d.1

Exercise

W-W-W-W-T-F?

Readings

Information Management: A Proposal (Tim Berners-Lee)

Weaving the Web (Tim Berners-Lee)

Resources

The first website (info.cern.ch)

Worldwideweb browser browser (emulator)

Line-mode browser (emulator)

Lynx browser (software)

Are.na w-o-r-l-d-w-i-d-e-w-e-b channel

For Everyone (video)

Tim Berners-Lee Invented the World Wide Web. Now He Wants to Save It (New Yorker)

Vague, but exciting . . .

https://princeton.zoom.us/j/98140026448?pwd=ZRjRgODHimRf47QaPKXXCZDUP9S36d.1

Exercise

W-W-W-W-T-F?

Readings

Information Management: A Proposal (Tim Berners-Lee)

Weaving the Web (Tim Berners-Lee)

Resources

The first website (info.cern.ch)

Worldwideweb browser browser (emulator)

Line-mode browser (emulator)

Lynx browser (software)

Are.na w-o-r-l-d-w-i-d-e-w-e-b channel

For Everyone (video)

Tim Berners-Lee Invented the World Wide Web. Now He Wants to Save It (New Yorker)