It was 2018, just before the end of summer, and I was in Post Mills, Vermont paging through old copies of Vermont Life magazine. My wife’s mother and father, longtime state residents, have saved copies of the magazine from the last 50 years or so. It’s published quarterly, each issue taking advantage of Vermont’s four crisply rendered seasons. A story might detail the comings and goings in the town of Corinth around a furniture maker’s workshop at the start of fall, or the raising, in early spring, of a round barn in Bradford. Each story is particular, and somehow each is also generic.

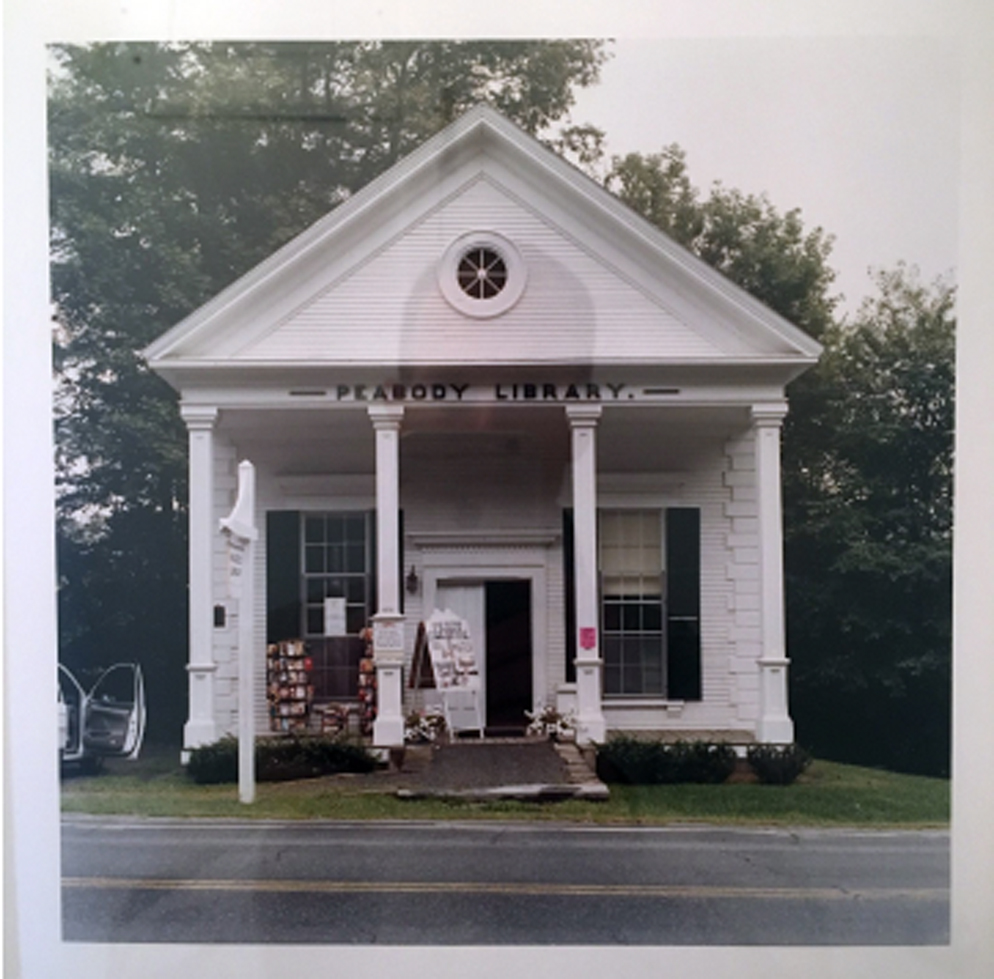

To read the magazine now in a small town in the state is like stepping into a time-shifted mirror. The towns of Vermont Life in 1968 look more or less like the current town of Post Mills. Like any one of the featured places, Post Mills is tiny (population 346) and picturesque. There’s an airport for small planes, gliders, and hot air balloons, a baseball diamond, a graveyard, a farmstand, a general store, and a small public library with a paperback lending rack on the porch. Corinth is 12 miles northwest, Bradford is 13 miles northeast, and in between is unblemished landscape.

I was flipping through the summer 1968 issue of Vermont Life when I was stopped by a small news item included on the last page. It read:

I recognized this future law as what would become the 1968 State Billboard Act (Title 10, Chapter 21, § 495). The statute prohibits the construction of all off-premise commercial signage in the state of Vermont and regulates the size and design of all commercial signage.

It’s an exceptional piece of legislation and a testament to the power of government regulation to attack problems that are too large or unwieldy to be solved another way. Visiting Vermont today, it’s visually striking to drive through a landscape untouched by commercial signs, or be in a public space without the clamor of so many advertising messages competing for your attention. The reclaiming of public space for the public in 1968, not to mention still, 50 years later, seems an impossibly optimistic action, usefully out of step with what has become the defacto trade of advertising for access that fuels our collective notions of public space in the United States today.

Continues in class ...

To read the magazine now in a small town in the state is like stepping into a time-shifted mirror. The towns of Vermont Life in 1968 look more or less like the current town of Post Mills. Like any one of the featured places, Post Mills is tiny (population 346) and picturesque. There’s an airport for small planes, gliders, and hot air balloons, a baseball diamond, a graveyard, a farmstand, a general store, and a small public library with a paperback lending rack on the porch. Corinth is 12 miles northwest, Bradford is 13 miles northeast, and in between is unblemished landscape.

I was flipping through the summer 1968 issue of Vermont Life when I was stopped by a small news item included on the last page. It read:

In spite of such pessimism, and similar doubts expressed by Samuel Ogden (page 16), it is possible a shining triumph will have been enacted when these words reach the reader. We’re speaking of Theodore M. Riehle’s proposal to ban all Vermont billboards and signs. Only signs allowed would be standard, state-owned directional signs, and the owner’s on-premises signs. At this writing, in January, Mr. Riehle’s bill, impossible as it seemed at first, appeared to have a good chance of passage.The tone was surprising and compelling. It seemed to be both a report on what had happened as well as a rather self-assured prediction of what would be soon to happen: a shining triumph will have been enacted when these words reach the reader. Further, from my comfortable position in 2018, I knew the prediction was correct.

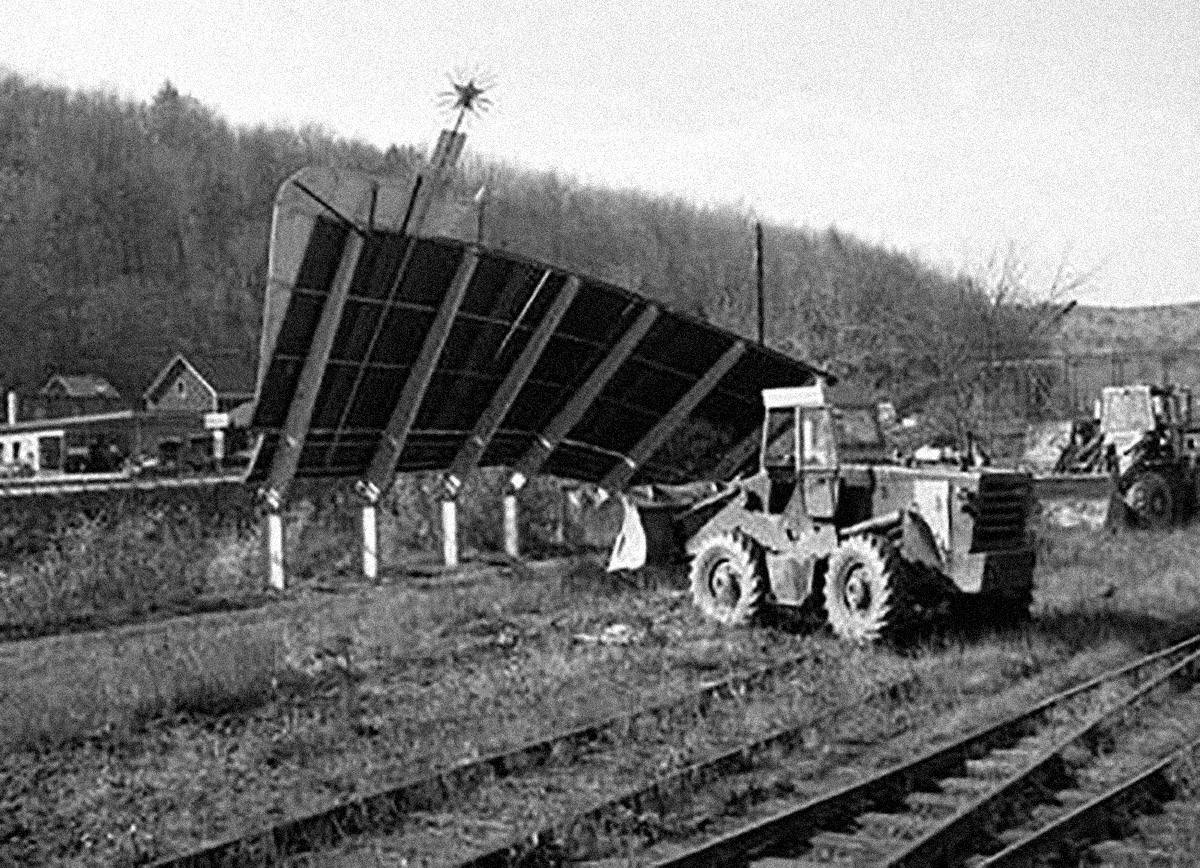

I recognized this future law as what would become the 1968 State Billboard Act (Title 10, Chapter 21, § 495). The statute prohibits the construction of all off-premise commercial signage in the state of Vermont and regulates the size and design of all commercial signage.

It’s an exceptional piece of legislation and a testament to the power of government regulation to attack problems that are too large or unwieldy to be solved another way. Visiting Vermont today, it’s visually striking to drive through a landscape untouched by commercial signs, or be in a public space without the clamor of so many advertising messages competing for your attention. The reclaiming of public space for the public in 1968, not to mention still, 50 years later, seems an impossibly optimistic action, usefully out of step with what has become the defacto trade of advertising for access that fuels our collective notions of public space in the United States today.

Continues in class ...

April 6, 2026

When It Changed

Reading

When It Changed, Part 1 (David Reinfurt)

When It Changed, Part 2 (Eric Li)

When It Changed, Part 3 (David Reinfurt & Eric Li)

Resources

When It Changed (Are.na channel)

Assignment

#3 w-w-w (continues)

When It Changed

Reading

When It Changed, Part 1 (David Reinfurt)

When It Changed, Part 2 (Eric Li)

When It Changed, Part 3 (David Reinfurt & Eric Li)

Resources

When It Changed (Are.na channel)

Assignment

#3 w-w-w (continues)